Using New Data and Novel Methods to Undertake Syndromic Surveillance to Identify Outbreaks of Food Poisoning (Rachel Oldroyd)

In October 2015, I started a part-time PhD in the Consumer Data Research Centre on the topic of Spatial Data Analytics for Food Safety. This is a White Rose DTC project which forms part of the Big Data and Food Safety Network, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). I’m roughly three months into what is going to be a long (five year) journey and although I’m trying to keep things general at the moment, I’m beginning to have a vague idea of where this project might take me.

Every year there are around 500 000 known cases of food poisoning in the UK and a further 10 million cases of gastrointestinal illnesses which may be food related. As the NHS recommends that people recover from mild-bouts of food poisoning at home, without visiting their GP, the true number of cases is hard to estimate via traditional methods. The Food Standards Agency (FSA) is a case partner for this project and they are particularly interested in how big data and social media can be used to more effectively monitor cases and outbreaks of food poisoning in the UK.

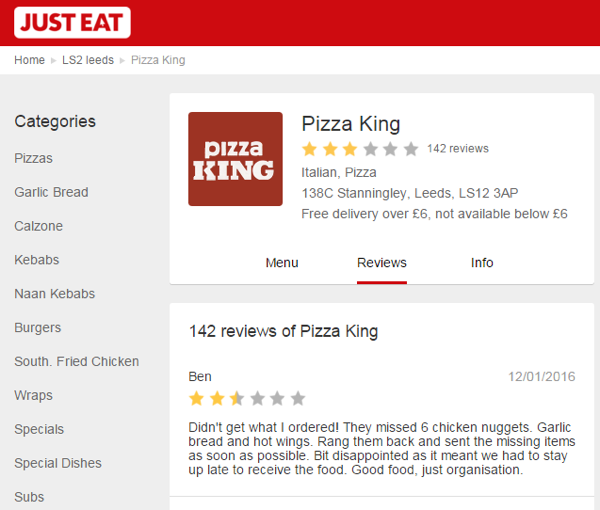

In the US, a number of studies have proved that Twitter and other online data sources can be used to undertake syndromic surveillance and identify whether people are suffering from known symptoms. Although the majority of these studies are Influenza focussed, the methodologies are also relevant for monitoring food-poisoning. These studies prove that a language model can be used to retrieve food-related messages from Twitter and, through natural language processing, identify if the author is suffering from a food-borne illness or not. In some cases, geo-located Tweets can be tracked to a specific restaurant location which is particularly useful for monitoring outbreaks of food poisoning, where more than one person has been infected at the same origin. Online restaurant reviews are somewhat simpler to process than Tweets, as they are restaurant specific and require less filtering. An author will often specify the type of food eaten which may be useful for identifying new food pathogen vehicles.

The timely reporting of foodborne illness is an essential component in avoiding a large-scale epidemic. Social media data and online restaurant reviews can be collected in near-real time and are therefore much timelier than traditional data sources such as GP visits or FSA inspection reports which can take up to two weeks to process. Despite their timeliness, information reported via Twitter and online reviews needs to be handled carefully. Food-borne pathogens have extremely varied incubation periods (typically between 1 and 28 days) making it difficult to attribute illness to a specific food establishment. For this reason, these data sources may not be suitable for monitoring food-borne illness caused by certain pathogens.

I’m still knee-deep in literature at the moment but the broad objectives of this project are:

- To evaluate the availability and quality of data from a variety of sources relating to demographics, movement patterns, social media messages, the quality and performance of facilities, and health outcomes;

- To construct spatial-temporal models of food safety across a country or region and to assess the effectiveness and robustness of that model;

- To explore the utility of the models as a means for targeting scarce resources and to suggest other means for the extraction of value from the application of this research.

In the next few months, I hope to start collecting online restaurant review data to carry out some preliminary analysis against the FSA inspection data. Watch this space!

Author: Rachel Oldroyd

Source: Salidek et al. (2013)